A Legacy Unearthed: Submitting My Family Tree to the Royall House Archives at Harvard

By Jamie Dykes

(Former student, Harvard Extension School & Harvard Kennedy School Executive Education)

In the early days of my academic life, sitting in the library of the Harvard Extension School, I could not have imagined that my own ancestry would someday intersect with the core of Harvard’s historical conscience. But here I am—more than a decade later—not only tracing my family roots back to colonial Virginia, but submitting part of that story to Harvard Law School’s archival Royall House records.

This isn’t just personal. It’s national. And like many Americans, I’m beginning to understand just how much history lives in our bones—quietly, until the archive is opened.

The Royall Legacy: A National Reckoning

Isaac Royall Jr., whose estate helped fund the founding of Harvard Law School, has long been a subject of moral and institutional reckoning. His family’s wealth was built through the exploitation of enslaved people in both Antigua and Massachusetts. The crest that once adorned the Law School shield bore his family arms—a symbol rightly retired.

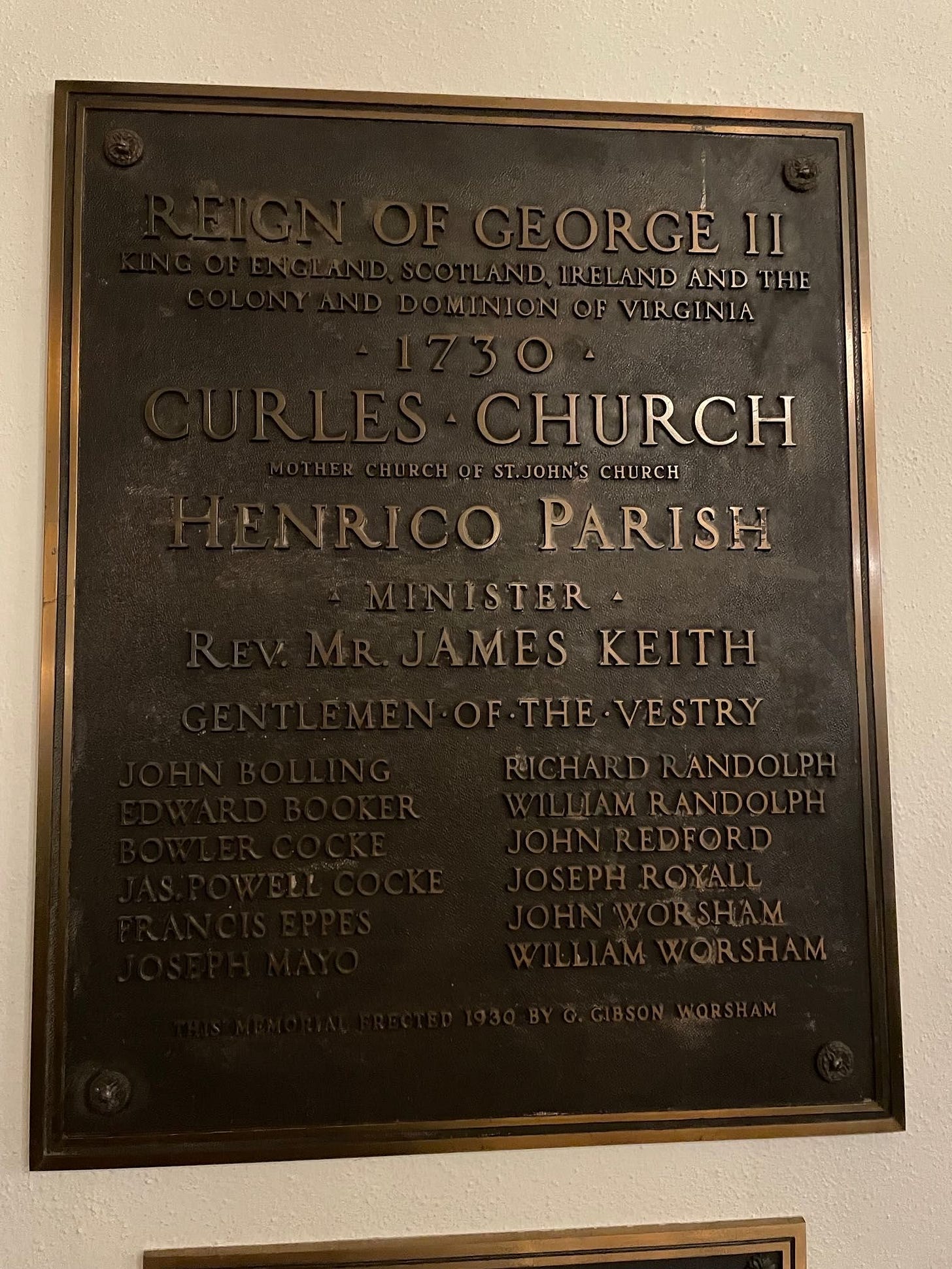

Yet what many don’t know is that the Royall lineage stretches deep into the Southern colonies, long before Isaac ever walked Harvard’s grounds. In tracing my own genealogy, I discovered I am a direct descendant of Joseph Royall, Isaac’s Virginia ancestor, who arrived in the colony aboard the Charitie in 1622.

Joseph Royall, my 10th great-grandfather, was a tailor-turned-planter who survived the 1622 Powhatan uprising and quickly ascended in landholding ranks. By 1635, he had secured over 1,100 acres on Turkey Island Creek in what became the Doghams Plantation. He married Katherine Banks, who after his death in 1655, remarried Henry Isham—establishing a matrilineal thread that links the Royalls, Ishams, Randolphs, and ultimately President Thomas Jefferson.

But my line didn’t continue through Isaac Royall Jr. It came through Katherine Royall, daughter of Joseph and Katherine Banks Royall. She married Richard Perrin, and from that union came a quieter line—one less likely to appear on institutional seals, but no less enduring.

Harvard, Memory, and Responsibility

I studied museum studies, American cultural history, and public administration across multiple Harvard schools. In these classrooms, we spoke often about interpretation, representation, and reconciliation. We debated what institutions owe the public—and what the public owes itself—in telling the truth about our shared past.

But what I’ve learned in the field—and in the family tree—is that those questions are no longer theoretical.

They are us.

They are our great-grandfathers whose names appear on land patents, plantation records, and probate inventories. They are the enslaved people unnamed in those same documents. They are the women—like Katherine Banks Royall Isham—whose multiple marriages created the scaffolding of elite colonial society, but whose autonomy was rarely acknowledged.

And they are the descendants like me, whose names were not carved into seals or etched into endowments, but whose memories live on—in the marrow, in the record, in the refusal to forget.

Excavation at the Royall House

While at Harvard, I took a course that explored the archaeology and symbolism of slavery in New England. We studied the excavation of the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, where over 65,000 artifacts were unearthed—material traces of two radically unequal lives lived in parallel.

The chamber pots stayed with me. Some were plain and utilitarian. Others, oddly decorative. You could imagine the quiet choreography of a maid’s day—emptying one, scrubbing another, returning it to a room she’d never be invited to rest in.

The skivvies, we learned, were always a promising place to dig. To the archaeologists, these personal remnants were rich in data. But to me, they were something else: signs of presence, care, autonomy, resistance.

We studied the “black domain”—spaces archaeologists now understand to have signified more than servitude. They represented survival, memory, and contested dignity. What was buried wasn’t forgotten. It was negotiated.

Women Remembered

If the Royall men carved their names into deeds and seals, it was the Royall women who carried the lineage forward.

Through Mary Perrin, Katherine Napier, Sarah Brock, and Martha Julia Bird, the women in my line survived wars, relocations, and silence. They kept houses, held land, raised children, and passed down stories in fragments. Stories that did not make it into history books—but did make it into me.

This is not a side branch. This is the inheritance.

Why I’m Making This Public

This is more than a submission—it’s a declaration.

We often wait for institutions to tell our stories. But I believe the time has come for descendants to bring forward their archives, to own our place in the record, and to ensure the stories of early America are not lost to the silence of private databases or locked genealogy sites.

This Substack is part of that mission. Over the coming months, I’ll be releasing records, relationship charts, probate trails, and land transfers that trace the Royall, Isham, Randolph, Jefferson, Perrin, and Cooke families—all of whom converge in my lineage.

These are not just names. These are stories of survival, exploitation, migration, and power. They shaped the landscape of early America. They shaped Harvard. And, through a long and sometimes painful arc, they shaped me.

Submitting to the Archive

In submitting this tree and its documentation to the Royall House Project at Harvard, I hope to accomplish the following:

Enrich public understanding of how the Royall legacy extended from Virginia plantations to New England philanthropy.

Provide verifiable genealogical records that connect Southern colonial families to the Royall line.

Offer a descendant’s perspective that is rooted in critical thought, not romanticism.

Bridge archival history with modern accountability, contributing to Harvard’s ongoing reckoning with its past.

As someone trained in both the stewardship of public memory and the mechanics of governance, I believe transparency and humility are critical. We cannot reshape institutions until we bring our full truths to the table.

A Living Archive

To Harvard: I submit this tree with respect, clarity, and an understanding of what this family has meant—both as builders and breakers of this nation’s early promise.

To the public: I offer this lineage not as a claim to grandeur, but as an invitation to look inward, to research your own, and to walk the balance of pride and accountability.

Final Words: I Am the Inheritance

My ancestors helped fund Harvard Law.

My ancestors were also legally bound in servitude.

My ancestors built homes that became historical landmarks.

And my ancestors lived lives small enough to disappear between records.

This is what legacy means. Not prestige. Not shame.

Just truth—and what we choose to build with it.

In my work today—developing financial tools that protect labor, reward human dignity, and resist economic extraction—I see the other side of that crest. The one not carved in marble, but made in memory.

Harvard didn’t know about me. But now you do.

—

Jamie Dykes

Museum studies. American culture. Public administration.

Harvard Extension School | Harvard Kennedy School Executive Education

2025

🗂️ Follow the archive releases and companion essays at:

📜 Submission to: Royall House & Slave Quarters Museum, Harvard Law School Archives